Other conceptual frameworks in IEHIAS

- The text on this page is taken from an equivalent page of the IEHIAS-project.

A range of different conceptual frameworks have been developed over recent years, aimed at summarising the relationships between environment and health. Many of these have been devised to help identify and select environmental health indicators, others to give structure to thinking about policies, others to help frame epidemiological studies. They can also be useful as a basis for issue-framing in integrated environmental health impact assessment, though care is needed to ensure that they are not applied too rigidly, and thus limit thinking.

One of the earliest, yet also most influential, frameworks in the area of environmental health was that proposed by Lalonde in 1974. This recognises four determinants of health: human biology, environment, life style and health care organisation. The framework has been adopted as an underpinning model for a number of environmental health initiatives, including that of the Dutch Centre for Public Health Forecasting. Subsequently, however, a more complex framework was proposed by Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991), distinguishing different layers of influence within the health sphere. The inner core consists of factors which are more or less fixed and immutable (age, sex and hereditary factors); surrounding layers define the factors (e.g. individual lifestyle and wider social, community and environmental influences) that could theoretically be modified.

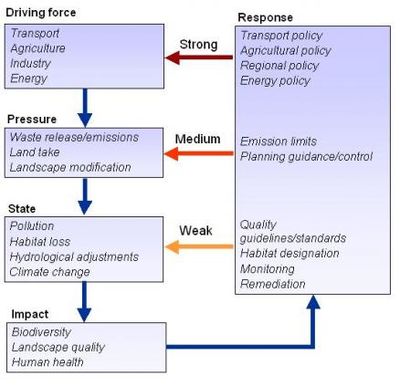

A separate approach to framing environmental health issues emerged from work to develop state of environment reports and associated indicators, and later as a basis for environmental assessment. In the 1970s, a simple framework was developed which recognised environmental impacts as a consequence of pressures (mainly from human activities), which cause changes in the state of the environment, and in turn led to policy responses. This Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model was widely adopted (e.g. by OECD and the US-Environmental Protection Agency). In time, however, it was extended to incorporate additional elements, relating to driving forces and impacts (the DPSIR model), and this was in turn modified to represent health issues more effectively by including exposures and health effects (the DPSEEA framework). More recently, also various other frameworks have been developed, targetted at more specific issues (see references below).

DPSIR

In the early years of envirnmental assessment, a relatively simple schema was used to help structure assessments and identify indicators - the so-called PSR (Pressure-State-Response) model, initially developed on behalf of the OECD. In time, the limitations of this became apparent, and a number of initiatives were started to devise something more appropriate. Out of these emerged the DPSIR framework, which was taken up and applied as a basis for assessment by the European Environment Agency.

As the diagram on the side indicates, this sees environmental impacts as originating in driving forces (D) such as industrial activity or transport, which lead to pressures on the environment (P) through emissions, land take etc, and thereby change the state of the environment (S) in different ways. These changes lead to a range of impacts (I), both on the environment and on human society (including health effects). Policy and other responses (R) are taken to control these impacts, targetted at different points in the causal chain. Notably, in the case of the environment, preventative measures (targetted at the sources) tend to be most effective, because these can avoid environmental damage. Later intervention, after damage has been caused, tends to be much less effective, because of ther cost and difficulty of cleaning up pollution, or repairing other forms of damage, once they have occurred.

DPSEEA

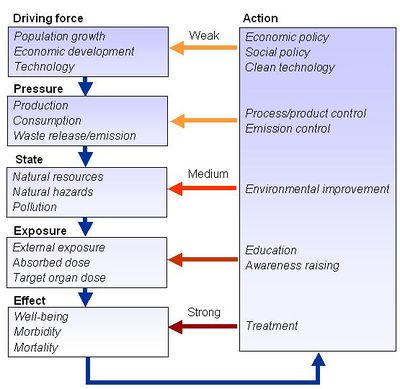

The DPSEEA framework was developed on behalf of the World Health Organisation, initially as a basis for developing enviromental health indicators. It adapted the DPSIR framework primarily by recognising the links from state of the environment through exposures to health effects; responses were relabelled as actions. It also extended the concept of driving forces backwards to represent the role of more remote, contectual factors such as social and economic development.

The framework thus sees health impacts as originating in these driving forces (D), which lead to pressures on the environment (P) in the form of production, consumption, waste generation etc, and their consequent releases into the environment. These contribute to changes in the state of the environment (S) - for example as environmental pollution or increased risks of natural hazards. Exposures (E1) occur when humans come into contact with these hazards, leading to potential health effects (E2). Policy and other actions (A) are taken to control adverse health effects. These may be targetted at different points in the causal chain. Later interventions (aimed at reducing exposures or mitigating the health impacts) may appear to be more directly effective and sometimes cheaper, because they can be targetted more directly at specific population groups and health outcomes. Preventive measures, in contrast, tend to involve somewhat blunter tools - but with the major advantage that they can control the problems at source, and often offer a wide range of other environmental and social benefits.

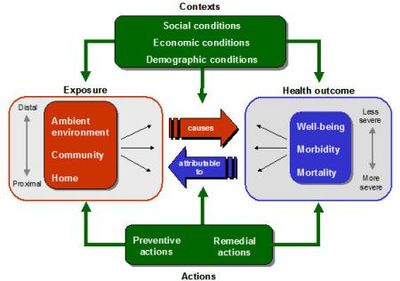

MEME

The MEME (many-exposures many-effects) framework was developed as a basis for selecting and creating indicators of children’s environmental health. It was a deliberate attempt to escape from the linear and pollution-based view provided by the DPSEEA (and other) frameworks, and to recognise the importance of behaviours and settings in determining exposures. It also highlights that the causal chain may be read in two ways: to identify the likely consequences of exposures (and thus predict health effects), or to track effects back to their causes (and thus attribute blame and define where preventive action might be necessary).

References

- Briggs, D.J. 2003 Making a difference. Indicators to improve children’s environmental health. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Corvalán, C., Briggs, D.J. and Kjellstrom, T. 1996 Development of environmental health indicators. In: Linkage methods for environment and health analysis. General guidelines. (Briggs, D., Corvalán, C. and Nurminen, M., eds). Geneva: UNEP, USEPA and WHO.

- Dahlgren, G. and Whitehead, M. 1991 Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm: Institute for Future Studies.

- European Environment Agency 2010 The European Environment - State and Outlook 2010. Copenhagen: European Environment Agency.

- Gee, G.C. and Payne-Sturges, D.C. 2004 Environmental health disparities: a framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environmental Health Perspectives 112, 1645-1653.

- Huynen, M.M.T.E., Martens, P. and Hilderink, H.B.M. 2005 The health impacts of globalisation: a conceptual framework. Globalization and Health. BioMed Central 2005.

- Kjellstrom, T. and Corvalan, C. 1995 Frameworks for the development of environmental health indicators. World Health Statistics Quarterly 48, ' 144-154.

- Knol, A.B., Briggs, D.J. and Lebret, E. 2010 Assessment of complex environmental health problems: framing the structures and structuring the frameworks. Science of the Total Environment 408, 2785-2794.

- Lalonde M. 1974 A conceptual framework for health. RNAO.News 30, 5-6