Environmental burden of disease calculation

| Moderator:Julle (see all) |

|

|

| Upload data

|

Environmental burden of disease calculation

This chapter provides information about methods to calculate the environmental burden of disease, and the assumptions and choices that need to be made. Table 2-1 provides an overview of these baseline assumptions underlying the calculations as performed in the EBoDE project. The remainder of this chapter describes the specific models used for calculating the EBD and explains the different parameters and data used.

TABLE 2-1. Baseline facts and assumptions underlying environmental burden of disease calculations as carried out in the EBoDE project.

| Parameter of assumptions | Choise made | Motivation | Remarks | |

| Year | 2004 | Most redcent year with relatively good data availability | Exposure trends were evaluated till 2010 for a qualitative policy analysis | |

| Environmental stressors | Benzene, dioxins (including furans and dioxin-like PCBs), second-hand smoke, formaldehyde, lead, noise, ozone, particulate matter (PM) and radon | |||

| Countries | Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands | Integration of national projects | EBoDE working group and methodology is open for other countries | |

| Age weighing & discounting | Main results without discounting and age-weighing; alternative results with discounting (3%) and age-weighing (standard) | Ethical reasons. Supplementary discounted and age-weighed results presented for comparability with WHO estimates | ||

| Standard Life Expectancy | 80 years for men and 82.5 for women | Comparability with WHO estimates | ||

| Lag time | Calculations carried out with and without lag times | For certain diseases there is a relatively long lag between exposure and the effect. When using discounting, the lag should be accounted for | Lag times are based on author judgement and serve as rough estimates | |

| Uncertainty analyses | Qualitative and partly quantitative | It is essential to assess whether the substantial inherent uncertainties affect the order of magnitude of the results or the ranking of stressors | Data availability and limited resources allowed only for qualitative approach. Additional quantitative analyses are recommended as a part of follow-up research |

Basic calculation of the environmental burden of disease

The DALY measures health gaps (i.e. years of life lost due to death or disability) as opposed to health expectancies. It measures the difference between a current situation and an ideal or alternative situation. The DALY combines the time lived with disability and the time lost due to premature mortality in one measure:

DALY = YLL + YLD

where: YLL = Years of Life Lost due to premature mortality. YLD = Years Lost due to Disability.

Years of Life Lost (YLL) in a case of individual death is calculated as the difference between the standard life expectancy at the age of death and the actual age at death. When population data is tabulated for age categories, YLL can be calculated as:

L = LE (agedeath, gender) -agedeath

The basic formula for calculating

the population-wide YLL is:

YLL = N x L

where: LE(age,gender) = life-expectancy at age of death, accounting for gender agedeath = age at death N = number of deaths in a given age category L = remaining years to standard life expectancy at age of death (in years).

Methods for calculating YLL are

further described in section Years of Life Lost, co-morbidity and multi-causality

To estimate the Years Lost due to Disability (YLD), the number of disability cases is multiplied by the average duration of the disease and a disability weight (see further discussion below). The basic formula is:

YLD = n x DW x L

where: YLD = Years Lost due to Disability n = number of incident cases. DW = disability weight. L = average duration of disability (years)

The formulas above describe undiscounted, non-weighted DALYs. DALYs are sometimes attributed a discounting rate, and weightings according to age, in which case the formulas become more complex. These so-called social preferences are discussed in section 2.3.

Disability weights

(DW) Disability weights are used to make different health effects with varying degrees of severity comparable. They are weight factors that reflect the severity of the disease on a scale from 0 (perfect health) to 1 (equivalent to death). These factors have been determined in expert panels using standardized surveys.

Duration estimates

(L) Besides disability weights, estimates of DALYs for morbidity (Years Lost due to Disability – YLD) also take into account the duration of the disease derived from health statistics, registries, expert judgments, etc. In some cases, prevalence data are used in burden of disease calculations instead of incidence data. In that case, the duration of disease is set to 1 year in the calculation, assuming a steady-state situation in which prevalence equals incidence times duration. For mortality, the duration estimate equals the YLL (Yers of life lost).

Models for estimating the environmental burden of disease

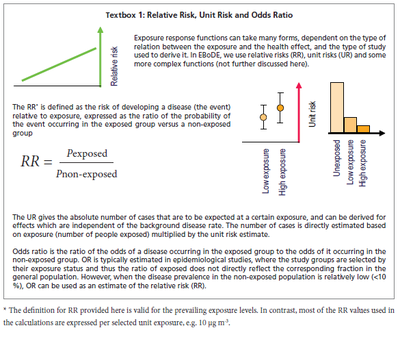

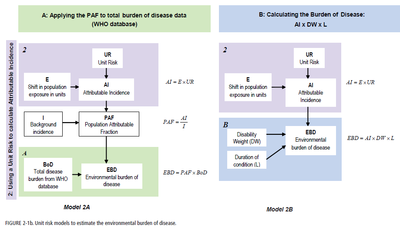

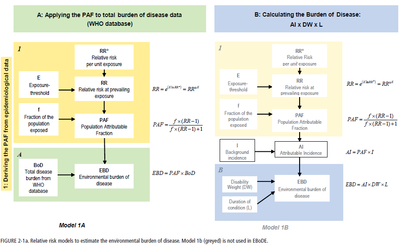

The general methodology for the environmental burden of disease calculations as carried out in EBoDE follows the Comparative Risk Assessment Approach (Ezzati et al., 2002; Prüss-Üstün et al. 2003). In general, information about population exposure, an exposure response function and (in some cases) background incidence data are needed in order to estimate the environmental burden of disease (EBD). In EBoDE, three different methods for deriving the EBD are used. They are presented in Figures 2-1a and 2-1b (methods 1A, 2A and 2B). Model 1B is not used in EBoDE, but complements the other three methods. The methods differ in how they derive the population attributable fraction (using a unit risk (UR) or a relative risk (RR) – see Textbox 1), and in whether burden of disease figures are derived from the WHO database or estimated using disability weights (DW) and duration factors (L).

- Model 1A is the primary model used in EBoDE. Exposure data and a relative risk derived from epidemiological data are used to derive the population attributable fraction (PAF). This fraction is applied to the burden of disease figures as given in the WHO global burden of disease database.

- In model 2A, the PAF is derived indirectly. The unit risk and exposure information are used to estimate the attributable incidence (AI). The PAF is indirectly estimated from dividing the total incidence by this AI. Subsequently, the PAF is applied to the WHO burden of disease data for both YLL and YLD.

- In model 2B, the AI is derived similarly as in model 2A. However, for the factors for which this approach has been used, no appropriate burden of disease data were available from WHO and the EBD was calculated by multiplying the estimated number of attributable cases with WHO disability weights (DW) and corresponding estimates of duration (L).

- Model 1B, which was not used in EBoDE, could be used when the PAF is derived using a RR risk, and the EBD is calculated using disability weights (DW) and estimates of duration (L).

The conceptual basis of the different methods is the same. Which exact method is chosen for a specific calculation mainly depends on the available data. In principle, these different means should come to the same end. If one would use all different approaches for the same calculation, they would ideally result in the same number. However, in reality it is hardly ever possible to perform all these different calculations because of unavailability of data. Even if possible, the different methods will rarely result in the same number. This stresses the importance of interpreting burden of disease figures as crude ranges and not as absolute infallible numbers. More information about uncertainty is presented in Uncertainty analysis.

Years of Life Lost, co-morbidity and multi-causality

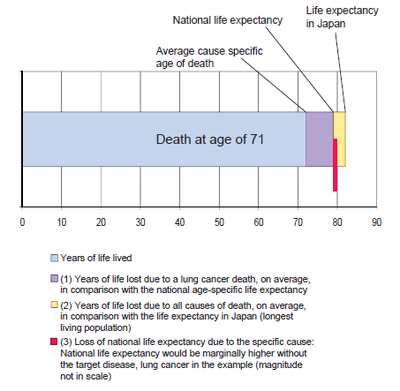

DALY calculations for mortality outcomes include an estimate of the Years of Life Lost, i.e. the number of years a person would have continued to live, had this person not died due to the environmental exposure. In the WHO Global Burden of Disease programme and in the current work a standard life expectancy, defined as a population with highest known life-expectancy, is used. This ensures that all populations globally are treated equally when addressing the disease burden.

However, in the current context where the focus is set on specific environmental causes of burden of disease, it can be argued that if all environmental causes of burden of disease were removed, the population in question still would not reach this optimal life expectancy. This is due to the fact that all factors affecting the population health (including also genetic factors, lifestyle, the health care system, etc.) contribute to the national life expectancy. Thus it could be argued that a national life expectancy should be used in estimating the impacts of given single factors. This difference in approaches is highlighted in Figure 2-2. In the EBoDE project we have chosen to use the standard life expectancy in order to allow for better comparison between countries.Figure 2-2. Estimating the years of life lost due to lung cancer.

Co-morbidity

Co-morbidity can play a role in estimating DALYs for morbidity. In the case of co-morbidity, people are not only affected by the disease under scrutiny, but are also weakened by other conditions. In industrialised countries, older people often have more than one disease. Severity weights do not take account of these co-morbid conditions (Gold et al., 2001). The disease burden is disease-specific and not individual specific, so adding up the severity weights for all diseases in a person could result in a weight of more than one, representing a state worse than death (Anand and Hanson, 1997; Schneider, 2001). Effects of co-morbidity can be relevant when looking at one person with several diseases. However, when estimating the burden of disease for a complete population, the effect of co-morbidity is not very influential.

Multi-causality

Multi-causality means that people have a single disease, but that this disease is caused by multiple factors. People may for example have lung cancer due to a combined effect of radon and smoking. If the exposure to radon would be removed, part of the lung cancer cases could be prevented. However, partly the same cases could in principle be prevented by quitting smoking. Because of this effect, which is called multi-causality, the estimated attributable fractions of these two separate causes for lung cancer are potentially additive to more than 100%. Therefore, there may be overlap in the estimated disease burdens of these two factors and they can not be summated without correction for this overlap. In case of mortality, this concept is also referred to as ‘competing causes of death’.

Correcting for multi-causality is most important when a significant number of cases are indeed caused by several of the addressed risk factors. It is however difficult to estimate exact effect of multi-causality, as the underlying epidemiology is lacking in many instances. In this project, multi-causality may affect the health impacts related to the joint exposure to outdoor air pollution and second-hand smoke, or to second-hand smoke and radon. The potential effect of multi-causality and overlapping health endpoints is not corrected for in our estimates of the burden of disease, but is discussed in the respective chapters. The stressor-specific figures should be interpreted as the burden of disease that could theoretically be prevented if the specific risk factor was removed.

Discounting, age-weighing and lag times

The environmental burden of disease estimated in EBoDE as DALYs are expressed in three alternative metrics. The differentiating weighing factors are described shortly in this chapter. The three metrics we used are:

- non-discounted, non age-weighted DALYs (i.e. health impacts occurring later in the future are counted with similar weight as immediate effects; health effects are weighted the same at all ages; no lag times are included)

- discounted and age-weighted DALYs (i.e. future health impacts are brought to present value assuming a constant discount rate of 3%; health impacts in older and younger people are age-weighted using the standard WHO procedure; no lag times are included)

- discounted and age-weighted DALYs with lag (i.e. future health impacts are brought to present value assuming a constant discount rate of 3%; health impacts in older and younger people are age-weighted and the delay from current exposure to the manifestation of the associated disease, e.g. cancer (lag) is included in the discounting procedure).

Discounting

When DALYs are discounted, future years of healthy life are valued less than present years. Discounting is based on the fact that people generally seem to prefer a healthy year of life immediately over a year of life lived in the future. In its Global Burden of Disease study, WHO applies a 3% time discount rate to years of life lost in the future. This means that a year of healthy life gained 10 years from now is worth 24% less than a year gained now. The use of discount rates can also be debated. Applying discounting to burden of disease figures is not favourable for children and future generations (Anand and Hanson, 1997; Arnesen and Nord, 1999) and preventive measures are devalued, as they cost money now while benefits will become apparent later (Schneider, 2001).

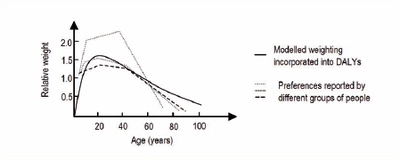

Age weighing

In the GBD study as done by WHO, a year of healthy life lived at younger and older ages is weighted lower than for other ages (see Figure 2-3). The motivation for such age-weighing is a number of studies that have indicated a social preference to value a year lived by a young adult more highly than a year lived by a young child, or lived at older ages. The social value of middle-age groups is considered to be greater, due to responsibility for their dependants, than the value of younger or older people. However, the use of age weights is highly controversial. Some critics state that it is unethical to value the lives of children and elderly less than other lives (Arnesen and Nord, 1999; Anand and Hanson, 1997; Schneider, 2001).